Interview with David Maynard, one of Redmaps first ever observers!

Emma Hamasaki, 30 Aug 2023.

David first joined Redmap in 2011. The out-of-range species sightings he has logged since then have made our database broader and more comprehensive, helping us determine what’s happening in Australian waters!

Here is a short interview we did with Dave to dive deeper into his life as an ocean enthusiast and the path he his taken as a marine scientist, including his role as a FRDC extension officer and his connections to Redmap.

-

Dave taking an underwater selfie in the Tamar - diving was one of two ways that David learned what species lived where. Image: David Maynard

-

David taking his son fishin gin Stanly hoping to catch the range extended Kin George Whiting. image: David Maynard

-

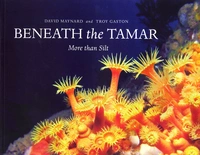

Beneath the Tamar – More than Silt by David Maynard and Troy Gaston

- To start off with, tell us just a little about yourself and your interest in working with fisheries and marine systems?

I love cataloguing life – I want to know what something is and where and when is lives. This has shaped my life and career.

As a kid in Brisbane, I was fascinated with native fish and spent all my time riding from creek to creek with my net and bucket. Not a lot was known about freshwater fish diversity in the early 80’s so it was a real mystery and new fish ID guides were hot property. If I wasn’t in a creek, then I was in a book shop or library searching for books on fish. This interest steered me towards the Australian Maritime College where I studied fisheries-related subjects in the early 1990’s. There is a big difference between hobby fishing and commercial fishing, but a common thread was the shear lack of knowledge of fish and invertebrate diversity.

After graduating I worked as microbiologist and export officer in a seafood factory. This was t too far removed from the sea and biodiversity. So, I was off to South Australia to work as a research scientist for the rock lobster industry – boats, fishing, and diving – it ticked some of my boxes. However, I returned to Tasmania to take up a position with the Australian Maritime College, lecturing into the degree program that I had graduated from. One of my core roles was to take graduates out on the vessel Bluefin and teach fisheries-related content. This involved identifying the catch, which is right up my alley – cataloguing life. I also dived a lot and photographed everything I found. This resulted in a co-curated exhibition and companion book titled Beneath the Tamar More than Silt. This educated the public about the biodiversity of our local estuary, kanamaluka/Tamar. I also lodged sightings with Redmap, helping to track species shifting south along Tasmania’s coast.

Next was Curator and Senior Curator of Natural Sciences at the Queen Victoria Museum in Launceston. This was an amazing opportunity to learn more about Tasmania’s wildlife, but now it was on the land, not in the water. I was lucky enough to have a great team specialising in insects and spiders. Over 10 years we charted their diversity across Tasmania and through time, finding many undescribed species, and observing changes in distributions related to climate change. This is a clear synergy with Redmap, just on land.

A significant part of my role was to raise community awareness of biodiversity and anthropogenic impacts. Climate change was (and still is) front and centre during my tenure and we had so many examples of changes in Tasmania’s environment, including Redmap data, to help educate the community.

My qualifications and experience in fisheries, and teaching, combined with my skills in hands-on science communication led me to FRDC.

- How did you come to be a FRDC extension officer, and what are the main objective of your role?

As the FRDC Extension Officer in Tasmania I am working with commercial, recreational, and Indigenous fishers, and the aquaculture sector, to help make them more sustainable and valuable through research and development. I am helping them shape their R&D needs and provide them with information about outcomes from existing research. Also, I have a couple of strategic issues to deal with – climate change, plastics and the longspined sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii). As well as talking with individual fishers, I also work closely with Government resourcemanagers (Marine Branch, NRE Tasmania), researchers (IMAS, CSIRO), sector representatives (TSIC, TARfish and the Land and Sea Aboriginal Corporation of Tasmania). Then there is the public; I will be organising a series of open house events to help the public access more information about marine systems. This is an important but complex topic that the public needs to appreciate as our oceans change, and the way we manage them. So, networking, relationship building, and putting people in contact with each other, and information delivery, are very big parts of my job.

- How long have you been interested in Redmap?

How long has Redmap been around?!? I can’t remember what contributions I have made but I do know that I was always using the resources and references to support my lectures. Particularly relating to climate change impacts on fisheries and aquaculture. I also direct public observations/questions to the website so that observations are captured, and the latest science is accessed.

- Have you shared the information found from Redmap to others? How did the community respond to Redmap and the information on species distribution?

The FRDC Extension Officer Network (a representative in each Australian jurisdiction) use the Redmap ‘Whats on the move around Australia’ poster at industry and public events to showcase how the climate is affecting species distributions. It’s a great resource and really opens up conversation.

- You must spend a bit of time around the ocean – have you noticed any changes in species distributions over the last decade or so, or any other changes?

YES! Having fished on AMC vessel Bluefin on and off for 30 years I can see dramatic differences in catch assemblages. Once common, high-volume commercial species like jackass morwong (Nemadactylus macropterus) and trevally (Seriolella spp.) are all but gone. Also, mainland species like King George whiting (Sillaginodes punctatus), yellowtail kingfish (Seriola lalandi) and snapper (Chrysophrys auratus) are now quite common in Tasmanian waters. Redmap helps us track these changes, but we know so little about invertebrate taxonomy and systematics that we cannot fully measure the changes that are happening in our oceans. It is very worrying.

- What do you feel is the main strength or benefit of Redmap?

Personal observations validated by experts which is then turned into peer reviewed publications. This is such an important outcome as it gets the information out of the grey literature and can be used by decision makers.

Have a look at David and Troy’s book ‘Beneath the Tamar: More than silt’